Ἡ Ῥωμανία πῶς σοι φαίνεται;

Στήκει ὡς τὸ ἀπ᾽ ἀρχῆς ἢ ἠλαττώθη;What do you think of the state of Romania?

Does it stand as from the beginning,

or has it been diminished?Doctrina Jacobi nuper baptizati, 634 AD, A.H.M. Jones, The Later Roman Empire, 284-602 [The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986, p. 316], Greek text, "Doctrina Jacobi Nuper Baptizati," Édition et traduction par Vincent Déroche, Travaux et Mémoires, 11 [Collège de France Centre de Recherche d'Histoire et Civlisation de Byzance, De Boccard, Paris, 1991, p.167], see here.

This good book by Bryan Ward-Perkins stands as a case study for some of the issues discussed in the essay, "Decadence, Rome and Romania, and the Emperors Who Weren't." Specifically, we must investigate the way in which the title is deceptive. The "Fall of Rome" here simply refers to the events of 476 AD, and the end of the Western Empire, which no one at the time would have regarded as the "Fall of Rome," but which have taken on that form in modern historiography, from which Ward-Perkins does not depart. Similarly, the subtitle referring to the "End of Civilization" only means the end of civilization, or its serious degradation, in Western Europe, or the former Western Empire, not in Europe as a whole or in the Eastern Roman Empire, which in 476 became the entire and only Roman Empire, with the regalia of the Western Emperors duly returned to the Roman Emperor in Constantinople. Retaining the characterization of the Eastern Empire as the "Eastern Empire," and not the whole Empire, after 476, is a usage designed to distance the surviving Empire from its identity and is common in modern historians. It is a way-station to the full alienation of the East as the "Byzantine Empire," which enables us to disparage (as, for example, a "pretense") or forget its Roman origin and identity. Ward-Perkins conforms to this approach, with its evident goals.

Yet, unlike some less scholarly writers, Ward-Perkins is aware of what was going on in the East, and how it survived, and one of the early illustrations in the book is actually of the  formidable Land Walls of Constantinople [p.35], whose cross-section we see below right in a treatment adapted for this site. These walls stood unbreached for more than a thousand years, until 1453. They had not been designed to withstand cannon balls.

formidable Land Walls of Constantinople [p.35], whose cross-section we see below right in a treatment adapted for this site. These walls stood unbreached for more than a thousand years, until 1453. They had not been designed to withstand cannon balls.

What is going on with Ward-Perkins perhaps is best introduced with an example:

The early Germanic Kings of Italy, and elsewhere, even minted their gold coins in the name of the reigning emperor in the East, as though the Roman empire was still in existence. [p.68]

Here we see the implicit assertion that the Roman Empire is not "still in existence," and that there is something bizarre about the German Kings putting the Emperor on their coins. However, the presence of the Emperor on the coins is the surest indication that the Germans themselves knew that the Empire was "still in existence" and that at its head there was an Emperor in Constantinople -- a city often called Nova Roma, ἡ νέα Ῥώμη, "New Rome," or even just Ῥώμη, "Rome." If Ward-Perkins is going to say something like this, he has some explaining to do. But he doesn't do it -- which, unlike the Germans using the image of the Emperor, is the peculiar thing here.

Ward-Perkins even allows:

By contrast, the eastern Roman empire (which we often call the 'Byzantine empire') did not fall, despite pressure from the Goths, and later from the Huns... Only in 1453 did the Byzantine empire finally disappear, when its capital and last bastion, Constantinople, fell to the Turkish army of Mehmed 'the Conqueror'. [p.2]

So it is not ignorance that induces Ward-Perkins to see 476 as the "Fall of Rome" as a whole -- although the "last bastion" was actually the Morea -- and he even uses the term "Byzantine" sparingly, with its introduction even qualified by a "we often call" it that, as though we "often" call it something else. Actually, Ward-Perkins often does call it something else, namely the "eastern Roman empire." What he does not call it is Romania, or Ῥωμανία, thus joining the ranks of Classicists and Byzantinists who scrupulously avoid letting us know the proper name of the Roman Empire, which is the country they are writing about, and is the name used in the era he is considering.

Despite his awareness of the East and its history, with some caution about its identity, Ward-Perkins nevertheless holds firmly to 476 as the "Fall of Rome" in general. Thus, he says,

Brittany and the Basque country were only ever half pacified by the invaders, while north Wales can lay claim to being the very last part of the Rome empire to fall to the barbarians -- when it fell to the English under Edward I in 1282. [p.49]

This can have been true only if the "Byzantine empire" was no longer the Roman Empire, or the "very last part of the Roman empire" would have been the Roman fortress of Monembasia, which was ceded by Thomas, the last Despot of Morea, to the Papacy in 1461. Yet just a few pages earlier, Ward-Perkins mentioned the fall of Constantinople in 1453. He never does say, "The eastern Roman empire, which we, properly and righteously, come to call the (miserable) 'Byzantine empire,' was not really the Roman empire anymore, which is why I say that the 'fall of Rome' was in 476." Ward-Perkins never says this, nor does he favor us with the slightest bit of discussion about the issue -- which involves the thorny question that, if Byzantium is not Rome, then when does it begin? Generally, "Byzantium" is begun with Constantine in 330 or even with Diocletian in 284, rarely with 476. This is all avoided just by ignoring it, which really is a grave oversight and even a lapse of responsibility in a book about the "Fall of Rome" in 476, which nevertheless contains enough information for us to know that this version and this date are problematic. It's like he hopes we don't notice.

Elsewhere, we see a casual reflection of Ward-Perkins' view that the fall was in 476, but there are also moments of ambiguity, or where he specifies the fall as in the "West." Thus, we get, "In the 1930s, the English mediaevalist Eileen Power wrote an essay about the late Roman empire and its fall" [p.173], where we can only take this to mean that the "late Roman empire," as a whole, fell. On the same page, however, we get a reference to André Paganiol and Pierre Courcelle as writing "in the post-war period" about "the fall of the West," but ending with a quote from Paganiol that, "Roman civilization did not pass peacefully away. It was assassinated" (i.e. by the Germans, like in 1940). There we seem to be given to understand that Roman civilization as a whole came to an end. Ward-Perkins' book ends with the qualification and the ambiguity, where he says:

The end of the Roman West witnessed horrors and dislocation of a kind I sincerely hope never to have to live through; and it destroyed a complex civilization, throwing the inhabitants of the West back to a standard of living typical of prehistoric times. [p.183]

Here we see the "horrors" and the "inhabitants" specified for the West, but with the ambiguity that the "complex civilization" as been destroyed, what? Just in the West? Or entirely? Nothing "complex" left in Constantinople, was it?

The source of the ambiguities or evasions in the treatment of Ward-Perkins is the confusion of two different issues. One issue is whether the Germanic invasions were some sort of peaceful transition in which not very terrible things happened and we have some sort of transformation in which everyone ends up reasonably happy.

| Peter Brown? | Bryan Ward- Perkins | the Truth |

|---|---|---|

| Germans, peaceful transition | Germans, no peaceful transition | Germans, no peaceful transition |

| Romans, political & cultural continuity | Romans, no political & cultural continuity | Romans, political & cultural continuity |

Indeed, Ward-Perkins has a bit of fun with that thesis:

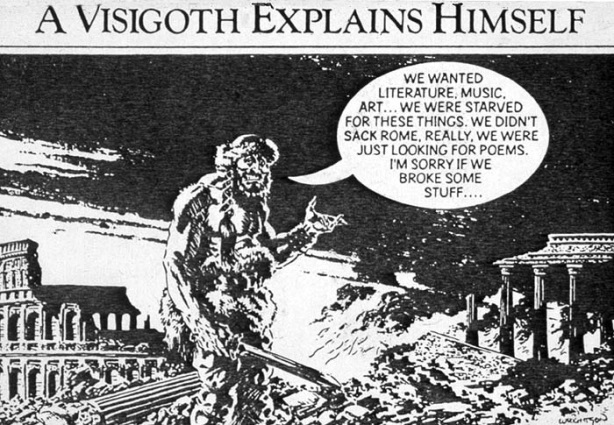

Some of the recent literature on the Germanic settlements reads like an account of a tea party at the Roman vicarage. A shy newcomer to the village, who is a useful prospect for the cricket team, is invited in. There is a brief moment of awkwardness, while the host finds an empty chair and pours a fresh cup on tea; but the conversation, and village life, soon flow on. The accommodation that was reached between invaders and invaded in the fifth- and sixth-century West was very much more difficult, and more intresting, than this. The new arrival had not been invited, and he brought with him a large family; they ignored the bread and butter, and headed straight for the cake stand. Invader and invaded did eventually settle down together, and did adjust to each other's ways -- but the process of mutual accommodation was painful for the natives, was to take a very long time, and, as we shall see in Part Two, left the vicarage in very poor shape. [pp.82-83]

This is not unfair. And Ward-Perkins marshalls impressive evidence against the idea of peaceful and friendly "accommodation." The Romans are conquered, and the Germans are not reluctant to let them know it. The material culture collapses, which Ward-Perkins illustrates most dramatically with the loss of quantity and quality of pottery, both as kitchen-wares and shipping containers -- as ancient liquids (oil and wine especially) and grains were moved in jars, not barrels or boxes. This indicates a loss of sophistication in consumer products, and the disappearance of commerce, which no longer exists in quantity. The disappearance of coinage, like that of shipping jars, also indicates the disappearance of commerce; and Ward-Perkins provides some nice graphs on the presence of coinage [pp.113-114], where what I have called a "rolling blackout" of trade crosses Europe all the way, by the mid-8th century, to the Aegean. It was in truth a "Dark Age," with literacy itself vanishing in Britain.

We can see an example of a viewpoint opposite to that of Ward-Perkins, where the vicarage is not much damaged at all by the guests, in the art history treatment, including several videos at YouTube, by art critic and art historian Waldemar Januszczak (b.1954). Januszczak actually calls his series of documenaries "An Age of Light," since he doesn't think that the Dark Ages were actually very "dark." He also doesn't like calling Germanic invaders "barbarians," because that is too negative and disparaging. Apparently, they were just as civilized as everyone else.

Januszczak does not consider the archaeological evidence, as Ward-Perkins does, of the decline in material culture and a cash economy. He also does not consider the main reason why the "Dark Ages" were always called "dark," namely the absence of historical records and other literature. Instead, he gets some mileage out of expanding the period beyond traditional boundaries. Thus, he says that the Dark Ages go from the 4th century to the 11th, ending specifically with the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. However, the 4th century, although marked by the catastrophic Battle of Adrianople, which, we can say, begins the Germanic invasions, nevertheless was not a time of decline in either material culture, money, historical records, or literature. Thus, causes of the Dark Ages may begin in the 4th century, but not the proper period itself.

Instead, the rolling blackout of civilization can be dated to Britain in 410, when Honorius informed that British that, after the rebellion of Constantine "III," who had taken the garrison with him to Gaul, the forces did not exist to reestablish the Roman garrison in Britain. They were on their own. The archaeology then seems to show that by 430 the economy was already collapsing, with coinage and ceramic production disappearing. By the next century, these stigmata had overwhelmed Gaul, and a century later, Italy, which had been damaged by the Roman reconquest and then was overwhelmed by the Lombard invasion in 568. Gaul did not drop out of history as much as Britain, and even the Lombards continued to mint gold coins, but things were going down hill.

At the other end of the period, Januszczak, in stretching things to 1066, must ignore the "Carolingian Renaissance" in the West and the "Byzantine Revival" in the East, both to be dated around 800. As it happens, commercial culture in Romania was reviving after never having totally collapsed; and historical records become better in both West and East; but with the Carolingians we witness a retrenchment more than a revival of the economy, as Charlemagne reduces the coinage to no more than a silver medium, without copper coinage for small purchases, or gold coinage for major transactions. This tells us what levels of activity the economy is not handling. For the economic revival of the West, it was not the Norman Conquest but the Crusades that made a real difference. Italian cities led the way to a genuine revival of commercial culture.

But it is rare to still see the "Dark Ages" used for the Carolingian period. The "Second Dark Age," characerized by Vikings, Arabs, and Magyars simultaneously ravaging Western Europe, has a claim to a status of its own; but by then the states and culture they were ravaging were already markedly different from the conditions of the 5th or 6th centuries. When the Vikings sacked the Lindisfarne monastery in 793, literate civilization there had already surpassed what it would have been in the same area under Roman rule. But Januszczak tosses Lindisfarne in the same sack with everything else from the "Dark Ages," without considering that its very existence would require a reconsideration of the terms of his analysis.

What may reveal a significant feature of Januszczak's point of view, however, is that, for all his admiration of the Lindisfarne Gospels, he fails to mention the work of the Venerable Bede, from the same neighborhood in Northumbria. Thus, the art historian looks at what can be construed as art, but he ignores what is otherwise substantial in the historical record and the literature, let alone the archaeology, by which the "Dark Ages" are most properly defined [note].

Ward-Perkins contrastss the economic loss in the West with that of the East:

But the Dark Ages catch up even to the East:

However, we notice that a cash economy remains in Constantinople, where a paid, professional military first is liquidated (c.668) and then revived (c.743). If a cash economy continues, this probably indicates a better experience in the hinterland of Anatolia, despite Arab raiding that makes life there more difficult, if not quite intolerable. Ward-Perkins says, "The imperial capital, Constantinople, may have been the only exception to the generally bleak picture" [p.126]. However, Constantinople could not have done it alone, and Ward-Perkins provides no information from the interior of Anatolia. With the Balkans and Greece overrun by Slavs, the day would soon approach, especially under Nicephorus I, when colonies from Anatolia will be moved and settled to repopulate Greece -- part of what Warren Treadgold calls "the Byzantine Revival." If the Empire can "revive" after 800, Anatolia must have been a reasonably healthy place to live in the 8th century. Anatolia remained a heartland of the Empire until the Turkish invasion after Manzikert in 1071.

While the contrast between the Empire in the East and the successor states in the West has its ups and downs, Ward-Perkins also shows us continuous economic activity at Antioch, which falls to Islam. Indeed, the failure of the German successor states to maintain the levels of Roman civilization contrasts dramatically with the success of the Arabs. At first:

However, this impression did not last. The Arabs, tribal as they may have been, were literate as the Germans really were not. Also, Islam came from centers of commercial culture. The Prophet himself had been a merchant, as no German king would be. Indeed, the German disdain for trade and money would persist in the aristocratic culture of Mediaeval Europe, where feudalism itself was a political and economic system based on the absence of a cash economy, trade, literacy, and cities. There is really no explanation for this except for the culture, with its adverse consequences, imposed by the Germans. Arab culture, however, fostered trade, a cash economy, and the development of large urban centers. This seems odd today, when Arab and Islamic countries seem to lag in economic development, but it is undeniable in the Middle Ages. Also, the aristocratic character of the Arabs, in which the conquerors remained distinct from the conquered, as in the German states, pretty much vanished with the Abbasid Revolution in 750. Converts to Islam became the equal of Arabs, and the Caliphs themselves soon were the children of Persian or Turkish concubines. In the German states, the problem was getting the Germans to conform to the religion of the conquered (whether that meant orthodox Catholicism or Christianity at all); but when this happened, it established no equality, and, generally, there was no intermarriage between aristocrats (i.e. Germans) and commoners (i.e. Romans).

The development of Islam reinforces the thesis that the German states represented a serious degradation of civilization. But the persistence of a cash economy in Romania also reinforces the truth that the survival of the Roman State also represented the survival of a more sophisticated level of civilization than the German states were capable of sustaining. And it does leave unexplained, and, in terms of the book by Ward-Perkins, even undiscussed, the identity of "Byzantium" as the Roman Empire. That is where the treatment by Ward-Perkins falls off the table.

A good indication of the evasion practiced by Ward-Perkins comes with what we see of Ravenna in the book. Which is, not much. We find Ravenna just four times in the index, with two other, unindexed occurrences that I have noticed:

Except for the manufacture of linen, Ravenna figures in the other references for one simple, objective reason: between 402 AD and 751, the city of Ravenna was the administrative capital of Italy and, until 476, for the Western Empire. This is even why we would find the church of S. Vitale there, with its remarkable mosaics of Justinian and Theodora. It would not be very difficult for Ward-Perkins to mention this, especially when he does mention that the Emperor Honorius "never felt strong enough to engage the Goths in open battle during their four years in Italy" [p.44]. Since Honorius isn't mentioned in relation to the sack of Rome by the Goths in 410, we might begin to wonder, "Where was he?" Well, of course, Honorius was hold up in Ravenna, where he himself had moved the capital, not from Rome, but from Milan. While Ward-Perkins tells us that the deposition of Romulus Augustulus in 476 "caused remarkably little stir" [p.31], he never does get around mentioning where this took place, which was in Ravenna.

So why this lack of simple information, which results, where they occur at all, in unexplained and opaque references to Ravenna? Well, it must be bound up in the issue of Roman identity that Ward-Perkins fails to discuss. When the identity of being "Roman" is cut loose from the City of Rome, which seems to have happened in the Third Century, we enter into a situation where it will be difficult to deny that those "East Romans" or "Byzantines" are properly Roman and that the Roman Empire did not Fall with the West. And with the "Fall of Rome," which is the topic and title of the book, there is a lingering assumption and preference that something as important as, indeed, the "Fall of Rome" should have happened at, well, Rome. That it didn't is awkward and, apparently, an embarrassment. Ward-Perkins seems evasive enough about it that we might say that it makes him uncomfortable. And this is of a piece with how he avoids the issue of Roman political and cultural continuity.

But there is nothing unusual about this, whether the context is popular culture, popularizing history, or formal scholarly history. Everybody has the same problem. They don't want Christian Romans in Constantinople to be Romans, regardless of their actual history, their own self-identification, or the view of their contemporaries -- for instance that they are

If we measure 'Golden Ages' in terms of material remains, the fifth and sixth centuries were certainly golden for most of the eastern Mediterranean, in many areas leaving archaeological traces that are more numerous and more impressive than those of the earlier Roman empire. [p.124]

In the Aegean, this prosperity came to a sudden and very dramatic end in the years around AD 600. Great cities such as Corinth, Athens, Ephesus, and Aphrodisias, which had dominated the region since long before the arrival of the Romans, shrank to a fraction of their former size -- the recent excavations at Aphrodisias suggest that the greater part of the city became in the early seventh century an abandoned ghost town, peopled only by its marble statues." [pp.124-126]

In many respects the Arab and Germanic conquests look similar -- both were carried out predominately by fierce tribesmen, and both took over the territory of ancient and sophisticated empires. At first Arab rule also resembled that of the post-Roman Germanic states in the West -- with a small military elite lording it over a large population that continued to live very much as before. [p.81]

, "the Rom(ans)," in the Qur'ân. While Ward-Perkins actually says, "I have never much liked the ancient Romans" [p.3], he falls more in the camp of, "Those Byzantines weren't Romans because we are." While he worries about the political incorrectness of using the term "civilization," he fails to worry about denying to the Ῥωμαῖοι their own "voice" and their own identity, which is a grave sin to the bien pensants of the modern academy, but which is a failing all but universal among Classicists and Byzantinists both. So Ward-Perkins gives us half a book. A good and honest treatment of the West, but with a certain mental and ideological blockage when it comes to the East and the whole Mediaeval future of Romania.

, "the Rom(ans)," in the Qur'ân. While Ward-Perkins actually says, "I have never much liked the ancient Romans" [p.3], he falls more in the camp of, "Those Byzantines weren't Romans because we are." While he worries about the political incorrectness of using the term "civilization," he fails to worry about denying to the Ῥωμαῖοι their own "voice" and their own identity, which is a grave sin to the bien pensants of the modern academy, but which is a failing all but universal among Classicists and Byzantinists both. So Ward-Perkins gives us half a book. A good and honest treatment of the West, but with a certain mental and ideological blockage when it comes to the East and the whole Mediaeval future of Romania.

Decadence, Rome and Romania, and the Emperors Who Weren't

If Waldemar Januszczak has some strange and distorted ideas about the "Dark Ages," we get something at least equally strange and distorted about the "Fall of Rome" from Edward J. Watts, a historian at the University of California, San Diego.

Here, I see Watts through the filter of a review by Peter Stothard -- Sir Peter -- a British journalist and author. Such a review gives us some idea what the book is about and whether it is worth buying and reading. As it happens, the book seems worthless, and it is even a little hard to tell what Stothard thinks about it himself.

What tips us off about the book is that Stothard begins by noting that Watts himself starts off talking about Donald Trump, and ends with Ronald Reagan, rather than in either place with the Romans. Watts has a political axe to grind, and it is a pretty nasty one. Thus, he speaks of misuse by "alt-right figures and white nationalists... of events from the fourth- and fifth-century Roman Empire to attack immigration in the twenty-first century."

Of course, few American conservatives actually attack "immigration," just the tolerance of illegal aliens and a failure to enforce immigration laws. But that is a consistent trope of the Left, to say that conservatives are "against immigrants," which is (in general) a lie, a misreprentation, and smear. But it is the Democrats' story, and they stick with it. As a deception, it seems to work well with the clueless.

Also, I still don't know what "alt-right" is supposed to mean; and actual "white nationalists" are so rare in American politics that it is also a lie, a misrepresentation, and a smear to speak of anyone beyond the infamous David Duke or explicit neo-Nazis (like supporters of Ḥamās?) in such a category. We have seen, however, that the poisonous Marxist "Critical Race Theory" can call absolutely anything "white supremacy" or "white nationalist," so no one in particular needs to be identified as such. By talking about moral character, even Martin Luther King Jr. was a "white nationalist."

We have seen elsewhere that the barbarian invasions of Rome have indeed at times been misrepresented as "immigration," even by Will and Ariel Durant. But I do not see this much elsewhere, and certainly not as part of current public political discourse in the United States.

The truth, of course, is that the Germanic invasions, if perhaps migrations, largely were invasions, with the occasional exception, like the Goths being allowed into the Empire in 376, with the Huns hard behind them. But when the Alans, Vandals, and Suevi crossed the Rhine on New Year's Day of 407, it was as much an invasion as that of the modern Germans in 1914 or 1940, if perhaps less organized.

So Edward J. Watts is a vicious and dishonest leftist. And whatever he gets around to saying about the Romans, chances are it will not be worth much. Which from Stothard's review, is pretty much the case.

Watts' basic thesis seems to be that those claiming to restore the glories of the past, in an age of decline, do that with what is actually "radical innovation" simply dressed up "as the 'defense of tradition'." Watts "sees a trail of victims -- immigrants, dissidents and the young."

The first villain we get is Cato the Elder, who fulminated against "immigrant" Greeks, who were undermining Roman virtue. However, it is not clear what kind of "victims" Cato left behind. We might blame him for the destruction of Carthage, but the Carthaginians were not "immigrants," "dissidents," or even "the young." As with the Greeks, it doesn't look like Cato's complaint discouraged either Greek travelers or the Romans who welcomed them to Rome. None of them seem to have been victims of anything.

From Watts we then get Sulla, who did leave a trail of victims, but this looks more like the party politics of developing Roman civil strife rather than something driven by political ideology -- except for the ideology of more political power for the Plebs, which drove the conflict and which Sulla, in the Senatorial party, opposed. So, I think, Sulla was not reviving the past but just opposing change. It might have had something to do with "dissidents," but not with immigrants or the young.

Indeed, "dissidents" sounds like the Gracchi brothers, who were both assassinated by Sulla's Senatorial faction. But then the "populism" of the Gracchi would seem to be more like Donald Trump, who Watts apparently wants to associate, rather than contrast, with Sulla. That isn't going to work. Watts himself, like Sulla, is a partisan and agent of the ruling class.

What doesn't get mentioned by Stothard is the more substantial ideology of idolizing the Roman Republic, by historians like Livy, after the Republic has fallen. Edward J. Watts is part of that idolization himself, since we have another book by him, Mortal Republic: How Rome Fell into Tyranny [2020]. So if, for Watts, the Roman Empire was "tyranny," he might like to do a bit of reviving himself.

In those terms, it seems odd for Watts to admire Emperors who were regarded even by the Romans as tyrants, like Caligula and Nero, who Watts wants to rehabilitate. Stothard seems puzzled by this also:

This is certainly a poor recommendation when we realize that all it means is that Caligula and Nero really had no political ideas at all, whether for "restoration" or in terms that they "prized stability and continuity," as Watts puts it. I never gathered that they "prized" any of these or their opposites. They prized themselves, which is what drove them to their destruction. A tyrant, pretty much by definition, is an egoist, who, if he expresses any ideology, has no more than a cynical regard for its usefulness to obtain power. Neither Caligula nor Nero were intelligent enough to have any such sophistication.

Antoninus Pius and Septimius Severus, who at least were not remembered as tyrants, also do not get associated with any ideas in particular. Sober government is what we can value in them, but then if Edward J. Watts thinks that the whole Empire is a "tyranny" that followed the Republic, he ought to be looking for some rulers with some robust notion of Republican government. We never do get any.

We then are given an odd window into the present. We are told about the "pressing modern crises -- modern 'poltical instability, environment degradation, wealth inequality and climate change'." Of course, if Watts thinks that something is needed to deal with these, it is going to require a bit more than a program "to bring society together." And if the wrong thing is, "like Sulla," to "create scapegoats," then it is odd that the discourse of "climate change" generally does exactly that.

Americans driving SUV's, or Americans simply using abundant energy and enjoying consumer abundance, are the perennial scapegoats of Environmentalism. But we don't get any more details about this in Stothard's review. Since recent "immigrants" flooding into the United States seem to be escaping the poverty of Third World countries, we might wonder if they will be happy with a country where energy and consumerism are under constant political attack, with residents expected to make do with less of everything in the future. If immigrants are going to be browbeaten into poverty, by the comfortable, privileged ruling class (like a professor at UC San Diego), they may as well go back home.

In Roman history, the mass movement that had no intention of reviving the past was Christianity. It is not clear how Watts can make sense of this. He apparently sees Diocletian as a bad guy, but then the Tetrarchy represented innovation in its own terms, while fighting against the religious innovation of the Christians. I do not see how that fits the cookie cutter paradigm that Watts wants to use. Stothard says, "Those who saw themselves as Romans had to choose between regret for temporal decline and rejoicing at spiritual progress." It may have been easier than that. "Decline," such as it may have been recognized, would be conceptualized as punishment for sin. This is already the analysis in the Old Testament for defeats of Israel and the Jews. Thus, the Romans simply "rejoiced" at being Christians, theatened by barbarians the same way that individuals are threatened by Satan. None of this fits in well with what I gather to be the analysis by Watts.

After we learn that Watts adds Commodus to the sad list of misunderstood Roman tyrants, we get a condemnation of the villain Justinian:

This passage is largely nonsense, and it is hard to know here whether the faults are those of Watts or Stothard, or both.

Justinian did not invent the "idea of a 'fall of Rome'." No contemporary in 476 thought that "Rome" had fallen. It was alive and well, thank you, with a legitimate Emperor in Constantinople. The "idea" of the Fall of Rome was "invented" centuries later, by Popes and Germans and Renaissance scholars who wanted to elevate themselves and delegitimize Constantinople. It was their own way having a Roman "revival," by simply erasing the last millennium of actual Romans.

And we see some of that hostile ideology in this passage. There never were any "Byzantines" as the word is used in this quote. I have examined this in a number of places, perhaps most succictly here. And the locution of "calling themselves Romans" is also typical of language seeking to dismiss and erase the identity of Mediaeval Romans, as discussed extensively here.

All that was needed at the time for Justinian to "justify" the restoration of the Western half of the Empire was that it properly belonged to the Roman Empire, not to barbarian invaders. If the Goths and Vandals had been defeated and prevented from establishing their kingdoms in the first place, as the Goths and Franks had been defeated in the 3rd century, we wouldn't think anything of it. Finally, we get two linked assertions. First that "hundreds of thousands of Italians... were erased." The City of Rome was damaged and depopulated in the course of its recovery from the Ostrogoths. But there is no evidence that this killed "hundreds of thousands of Italians." The population of Italy declined in the Dark Ages because the economy declined, as it did everywhere under German rule. The later advent of the Lombards, fragmenting the peninsula, prevented the full revival of Italy under Roman government, although we see pockets of commerce in cities like Naples and Venice, not to mention Sicily.

Similarly, "centuries of Roman law were erased." This is absolutely absurd. Roman law survived because it was indeed Justinian himself who had it codified and copied. How any informed historian can then say that the law was "erased" by Justinian clearly doesn't know what he is talking about. If this is what Edward J. Watts says, we cannot rely on anything he says.

So what we get from Watts is a distortion even worse than with Waldemar Januszczak. It was Justinian (and perhaps Donald Trump), rather than the German invaders, responsible for the destruction, decline, and misery of the Dark Ages. Perhaps he would like to blame the German invasions of 1914 and 1940 on Justinian too, and Trump.

The classic "Decline and Fall" analysis, of course, comes from Edward Gibbon. It is not clear to me how Gibbon's "triumph of barbarism and religion" contributed to Roman decline in terms of the analysis of Edward J. Watts. What Stothard says about Gibbon doesn't even mention Watts, so we are left to guess. Stothard does address the same issue as Bryan Ward-Perkins above, of the movement to see the barbarization of Roman lands as "mostly by negotiation," "transition," and "accommodation." Stothard refers to Ward-Perkins explicitly and seems to agree with him. Where Watts stands in this debate, I don't see any indication.

Gibbon, of course, was part of the Enlightenment project that critiqued monarchy and sought to revive Roman Republicanism, producing both an American and a French Republic. It sounds like that would be a kind of Original Sin for Edward J. Watts; and in fact the French Republic did leave a trail of victims, while the Left sees a similar trail, of the "oppressed," left by the American Republic. Which is why they want to destroy it. Edward J. Watts, in his own way, may be part of that project. So this must prove for Watts that revivals are bad.

Yet, as noted, Watts himself describes the fall of the Republic as leading to tyranny. And Emperors like Caligula, Nero, and Commodus would be paradigmatic exemplars of such tyranny. But Watts likes them. So I'm not sure what his story would really be.

After Bryan Ward-Perkins, we get back to Watts, with the reference quoted above about "alt-right figures and white nationalists." We do learn that he does follow Roman history, like Gibbon, all the way down to the Palaeologi. He finds another villain in Michael Palaeologus, who apparently counts as bad for expelling the Crusaders and "restoring" the Empire at Constantinople. We aren't told any of what the "sins so great" were that he committed; but we might guess that reviving the Roman state alone might be enough to damn him in the eyes of Watts.

Finally, we have the odd characterization of the German Emperor Maximilian:

The final falsehood here is so egregious that it must be considered first. The title "Emperor" went from Maximilian to his grandson, the Emperor Charles V, and then to his other grandson, Ferdinand I. There was no "rival family," and, of course, Stothard cannot name such a family. The title remained with the Hapsburgs, with just one exception, until the Empire was abolished by Napoleon in 1806.

This is so wrong that we must wonder if this is really what Stothard has gleaned from Watts' book. It is damning, on the one hand, for both of them, if Stothard has gotten it right, or just for Stothard, if he has become confused and otherwise doesn't know about the matter independently. But it is a shocking absurdity, which no one even slightly familiar with Hapsburg history can have said.

Otherwise, it is hard to recognize that we are actually hearing about Maximilian, who can scarcely be credited with doing anything to effect a "violent destruction of an existing political order." The Hapsburgs, indeed, and Maximilian in particular, are credited with marrying, not fighting:

The strong wage wars. You, happy Austria, marry. Thus, a new political order was created when Maximilian married his son to the Heiress of Spain, which made the grandson, Charles, King of Spain, with vast new possessions in the New World. The lines of Austrian and Spanish Hapsburgs dominated most of the next two centuries of European history.

Machiavelli didn't think much of Maximilian, because he didn't fight or trick his way to power. If Maximilian wanted Constantinople, he certainly never did anything about it. Machiavelli liked Ferdinand of Aragon better. But Ferdinand's kingdom and all his achievements ended up in the hands of the grandson of Maximilian, thanks to the marriages -- while brother Ferdinand married his way, with some fighting, into the kingdoms of Hungary and Bohemia.

Perhaps Watts, or Stothard, is actually thinking of the original Rudolf of Hapsburg, who was accused by Dante of tending to his own family interests and neglecting his duties as Emperor. After him, the Crown passed to Adolf of Nassau, who thus qualifies as from a "rival family." But if Watts has confused Rudolf with Maximilian, this doesn't make him any better as a historian.

Should the carelessness about history that we see here, particularly in regard to Justinian and Maximilian, be characteristic of the book by Watts, and not somehow an artifact of the ignorance of Peter Stothard, this means that Watts is not a good or even a reliable historian. Since his political purposes are pretty obvious, this means that he is little more than a biased hack writer. His book is likely to be of no value whatsoever, making no real contribution to scholarship or our understanding of history.

The Fall of Rome, and the End of Civilization,

by Bryan Ward-Perkins; Note

"The Road From Ruin," by Peter Stothard, The Wall Street Jounral, September 25-26, 2021, C7; "Books," Review of The Eternal Decline and Fall of Rome: The History of a Dangerous Idea, by Edward J. Watts, Oxford, 2021

These men may have been vicious fantasists, claiming divinity and artistic genius for themselves, but they did not inflict a political fantasy of restoration.

Justinian (527-65), though less widely known, is one of Mr. Watts' worst villains, inventing the idea of a "fall of Rome" in 476 in order to justify the Empire's restoration from the east. The Byzantines would go on calling themselves Romans, but hundreds of thousands of Italians and centuries of Roman law were erased.

But that they were defeated later, by Justinian, and their kingdoms destroyed, somehow rubs many historians the wrong way. How dare Justinian reverse the decision of history and erase those triumphant barbarians! They wrote poetry! To Mary Beard, it's "quite unfair"!

But that they were defeated later, by Justinian, and their kingdoms destroyed, somehow rubs many historians the wrong way. How dare Justinian reverse the decision of history and erase those triumphant barbarians! They wrote poetry! To Mary Beard, it's "quite unfair"!

The Habsburg emperor Maximilian (1508-19) hoped to regain Constantinople and once again used "the idea of Roman restoration to justify his violent destruction of an existing political order." But Maximilian had to balance his responsibilities as Holy Roman Emperor against his duties as a Habsburg. Family land and money would go after his death to his descendants. The title of emperor could be given to a rival family.

Bella gerant fortes. Tu felix Austria nube.

Nam quae Mars aliis, dat tibi regna Venus.

Thus the kingdoms that Mars gives to others, Venus gives to you.Copyright (c) 2021, 2025 Kelley L. Ross, Ph.D. All Rights Reserved